After eighty years of fragile peace, the Architects are back, wreaking havoc as they consume entire planets.

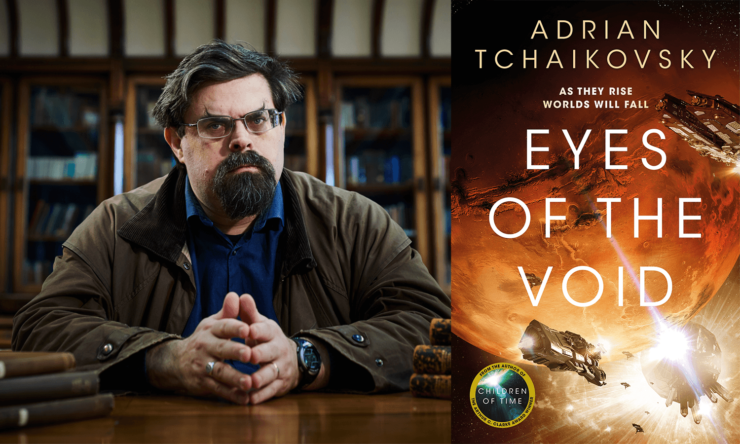

We’re thrilled to share the cover and preview an excerpt from Eyes of the Void, the second installment in the Final Architecture space opera trilogy from Adrian Tchaikovsky. Eyes of the Void by will be published on 28th April 2022 by Tor UK / Pan Macmillan. Preorder this title now!

After eighty years of fragile peace, the Architects are back, wreaking havoc as they consume entire planets. In the past, Originator artefacts—vestiges of a long-vanished civilization—could save a world from annihilation. Yet the Architects have discovered a way to circumvent these protective relics. Suddenly, no planet is safe.

Facing impending extinction, the Human Colonies are in turmoil. While some believe a unified front is the only way to stop the Architects, others insist humanity should fight alone. And there are those who would seek to benefit from the fractured politics of war—even as the Architects loom ever closer.

Idris, who has spent decades running from the horrors of his past, finds himself thrust back onto the battlefront. As an Intermediary, he could be one of the few to turn the tide of war. With a handful of allies, he searches for a weapon that could push back the Architects and save the galaxy. But to do so, he must return to the nightmarish unspace, where his mind was broken and remade.

What Idris discovers there will change everything.

Adrian is the author of the critically acclaimed Shadows of the Apt series, the Echoes of the Fall series and other novels, novellas and short-stories. The Tiger and the Wolf won the British Fantasy Award for Best Fantasy Novel; Children of Time was awarded the Arthur C. Clarke Award for Best Science Fiction Novel. This was in the award’s thirtieth anniversary year.

PROLOGUE

Who’d have thought crazy would turn out to be such valuable cargo?

Uline Tarrant was a rank opportunist. If you were a spacer it was a virtue. That meant when half of her acquaintances were tearing their hair and prophesying the end of all things after the clams took over, she was repurposing her business and making money. So, the former Colonies world of Huei-Cavor had voted to secede and join the Hegemony. They were now notionally ruled by the weird-ass shellfish-looking Essiel. Did that mean she couldn’t turn some Largesse, or at least get a toehold in the complex credit system the Hegemonics used? No it did not. Because one thing the upper crust of Huei-Cavor’s new cultist administration had was wealth, in whatever form you liked. And apparently spending it on conspicuous acts of piety was absolutely what they were all about.

This conspicuous piety that paid for her fuel and running costs was pilgrimage. She’d made it her speciality. If you were a devout worshipper of the Essiel, you went to places that were supposedly important to them. You meditated there and bought tacky little souvenirs, and probably met some useful people with good business connections. Uline wasn’t convinced that the whole thing was anything more than just some weird graft-turned-old-boys’-network to be honest. Religion wasn’t a thing she had much time for. Prayers didn’t fix spaceships.

She’d got her cargo hold fitted out with two hundred suspension beds, and they were all full. Anyone on Huei-Cavor who wanted to advance their social standing was getting in on the cult game, and that didn’t just mean wearing the red robes. Entire wealthy families were simply thrusting legal tender into her account for the privilege of being sealed in a robot coffin and hauled across the Throughways deep into the Hegemony. And, it turned out, if you were carrying accredited pilgrims, none of the weird-ass alien gatekeepers there asked many questions. She wondered if the spooks back at Mordant House knew that, because it seemed like a hell of a gap in Hegemonic security.

Her current target was some world called Arc Pallator. She’d never heard of it. The limited data said it was basically desert and canyons, nowhere she’d want to set foot on. She didn’t have to, though, there were orbitals. It was some big shot sacred site. Let the pilgrims deal with the heat and the dust, so long as they had the kind of crazy that paid up front.

They’d come out of unspace a respectful distance from the planet. The usual polite Hegemonic requests for ID were on her board when she shambled into the two-seater cupboard that passed for a command pod aboard the Saint Orca—that ‘Saint’ was added when she got into the pilgrimage business. Uline had only the loosest grasp of how godbothering worked, but she knew you stuck Saint in front of things when they were holy. The ship’s only other crewmember was already there, having never left but just powered themself down for the unspace trip. Tokay 99, as the Hiver called themself, waved a twiglike metal limb at her and she rapped them companionably on their cylindrical body.

She let the locals know who they were, sending over all the usual incomprehensible data that apparently allowed her to gad about inside the Hegemony. Everyone told you horror stories about how mad everything was here. Back before the secession she’d never have dared put the Orca’s nose inside their borders. She’d missed out on so much good business.

The local orbitals always wanted to do some kind of chit-chat with the pilgrims, so she woke a handful of this lot’s leading lights as the Saint Orca cruised in-system. Soon enough they were crowding her command pod, drinking her cheap kaffe and exchanging gnomic wisdom with docking control. A Hegemonic dealing with another cultist seemed like a combined politeness and Bible study contest. Except instead of a Bible, it was whatever cult wrong-headedness these loons had cooked up together to explain why they’d signed themselves over to a bunch of high-tech shellfish.

‘Got yourselves a busy crowd here,’ she noted. ‘High season for the faithful, is that right?’ There were plenty of other ships jockeying about waiting for docking and landing privileges. Some of them were the inscrutable Hegemonic ones that might have been haulers or luxury yachts, or moon-busting warships for all she knew, but others were human-standard. She even recognized a couple as distant acquaintances in the trade. Everyone wanted to come to touch the holies on Arc Pallator.

‘Crowded down there,’ Tokay 99 agreed. They’d brought up a display of the single human-habitable settlement, populated by who knew how many thousands and precisely zero sane people. Uline shared a look with them. She had more in common with their cyborg-insect colony intelligence than she ever did with her human cargo.

‘We are being instructed to stand by for a visitation,’ the senior cultist said. One of the others was fitting an even fancier collar to him, big enough that it brushed the ceiling of the cabin, as well as draping him with some cheap-looking bling jewellery.

‘So that means… what? Customs inspection? We got a problem?’ Uline asked.

She saw the faintest hint of doubt on the man’s face. ‘I… am not sure. But more than that. Something special. A visitation. I’ve been to a dozen pilgrimage sites and never heard that before.’

‘That means one of the—’ calling them clams wouldn’t exactly go down well— ‘one of your Essiel’s turning up?’

‘Oh no,’ the man said fervently. ‘If it was, they would have announced the full descriptor and titles of one of the divine masters.’ His eyes were fifty per cent naively earnest and the rest pure bobbins. She wanted to tell him, Look, they’re clams. You’re kneeling before an altar that’s mostly all-you-can-worship seafood buffet. But, because she was a respectable businesswoman, she said none of it.

Tokay made a querulous chirping sound. ‘You attended to the sensor suite errors?’

‘I did.’

‘By way of a qualified station mechanic as per our request,’ they pressed.

‘I fixed them myself. That’s better. It means we don’t get rooked by some kid who was sucking his ma’s teat when I was learning how to fix things.’

‘Anomalous gravitic readings on the long-long scan,’ the Hiver told her, ‘suggest your time could have been better spent in haggling.’

‘Now you listen, this is my ship and we’ll…’ Her eyes were dragged to the readings Tokay had pushed over to her board. ‘We’ll…’ she said again.

The Architect appeared between Arc Pallator and the system’s sun, breaching from unspace in a maelstrom of rainbows as the star’s light refracted in all directions out of its crystal form. Far closer than she’d ever heard they came. Weren’t they supposed to turn up way out-system? To give people a chance to get away?

‘Right, right, right.’ She just stared as her mouth made mindless words. The cultists had all gone deadly quiet and still, which meant maybe they weren’t as mad as all that. ‘Right. We need… we can… Damn, they’re lucky there’re so many ships here already. We can take…’ Trying to do the maths in a head just cracked by the sheer fact of it. An Architect, like in the war. Here in the Hegemony where they weren’t supposed to appear. ‘We can take another hundred, standing room only between the pods.’ She was aware the lead cultist was talking to ground control or whoever it was. ‘You tell them… ah… if they can get people up to orbit, we’ll load until we’re groaning. We’ve got…’ The Architect had now begun a stately cruise outwards from the sun, headed squarely for Arc Pallator. ‘We’ve got…’ Not enough time. No time at all. Oh God. Oh God. ‘We’ve got to get out of here.’

‘There is a proclamation,’ the lead cultist said reverently.

‘I’ll bet there is.’

‘From The Radiant Sorteel, the Provident and the Prescient,’ he told her, meaning one of the actual Essiel had weighed in on this one.

‘They got a radiant evac plan?’ She couldn’t take her eyes off the approaching Architect. Her hands were shaking over the displays on her board.

‘You and all your fellow pilots are forbidden from leaving until your holy work is done,’ the cultist said. ‘We are commanded to go down to Arc Pallator and stand amongst the holy ruins. We are chosen for this test of our faith, my brothers and sisters.’

‘No way in hell,’ Uline snapped. ‘We’re going, right now. Look at it! Look at the goddamn thing!’ She’d never seen one

before. She’d only seen mediotypes, heard war stories. Glimpsed the wrecks of ships and worlds. The death that had come for Earth and not stopped coming for a century of war. The death that had come back, when all she wanted was to have lived and grown old and died, and to have never had this monstrosity in her sight. ‘Look at it,’ she repeated, just a terrified moan.

‘Judgement,’ the cultist breathed. ‘A test of our fidelity to the words of the divine. We must go to the world. We are called.’ There was a new edge to his voice. ‘If you deviate from the prescribed flight plan I am instructed to say that will constitute breach of contract, and also blasphemy against the wishes of the Divine Essiel. Your drives will be disabled and you will not receive recompense, nor will you be able to leave the system.’

Tokay let out a thin whine, nothing she’d ever heard from a Hiver before but it communicated fear very eloquently. She felt it too, exactly that sound, inside her gut. She wanted to sob. Scream at them. Tell them their clams were crazy and they were suicidal. She wasn’t being paid enough to haul martyrs-in-waiting. But the Essiel could do all they’d said. They had weapons she couldn’t even understand. Everyone knew that.

She brought the Saint Orca back on course, heading for the orbital positioned directly over the single city. The city of people who’d soon be looking up at a new crystal moon. Briefly, she reckoned. Before their faith was tested the hard way and they became nothing more than disassociated strands of organic material. The problem with saints, she recalled, was that you had to be dead to be one. Yet all around her every pilgrim ship was still gliding in for docking, taxiing in a long queue around the single orbital, or else beginning the long, slow descent into atmosphere. And the Architect accelerated towards them, ready to drop into its own fatal orbit and obliterate every last one of them.

PART 1: HISMIN’S MOON

1

Havaer

‘That,’ Havaer Mundy said to himself, ‘is the Vulture God.’

There were a good seventy ships and more docked at Drill 17 on Hismin’s Moon; standard procedure to run a scan of them all as his craft, the Griper, came in. The onboard computers were still complaining from being bootstrapped back to functionality after exiting unspace, so Havaer had taken on the scanning work himself, letting his team stretch their legs and get their heads together. They were all outfitted as the rougher sort of spacers: half-sleeved long-fit tunics, trousers that always seemed too short to someone used to core-world suits, and of course the omnipresent sacred toolbelt, and the plastic sandals. All printed on-ship and scratchy with poor fabric. Just another crew of reprobates out on the razzle on this bleak satellite.

They had taxied over the docking field, liaising with the drill rig’s kybernet about the required approach and landing fees. Out here everything was cheap, life included, but nothing was free. Havaer had the ship check off each and every other visitor, finding that no fewer than nine vessels were on the Mordant House watch list. If he’d been here just on a bit of a career-building jolly, he’d have had quite the choice of who to go after. Although, given spacer solidarity, a heavy hand might have set him against the entire populace of the rig. Which was about ten times the number actually needed to do any drilling, because this little den of iniquity had become quite the fashionable dive since the destruction of Nillitik.

The Architects had returned. As though trying to erase the history of their previous failure, they’d been busy. First they had descended upon Far Lux where, half a century before, three Intermediaries had met with them and ended the first war. This time, almost nobody had got off-planet before the end.

Over the next months, they had appeared in the skies of a handful of other planets, without pattern, without warning: jagged crystal moons emerging from unspace. They’d been turned away from the Colonial heart of Berlenhof but nowhere else had been as lucky. The war was back on, and everyone had got out of the habits that had saved lives back in the first war. As many lives as had been saved, amidst the colossal death toll. The whole of humanity had to relearn sleeping with a go-bag and always knowing the fastest route to the nearest port. And not just humanity, this time.

Amongst the Architects’ recent victims, the least regarded had been Nillitik. It was within a string of connected systems that the Hanni and Earth’s explorers had discovered in the early days of their meeting. For a while they had been thought of as a kind of border-space between the two species. Except every discovery of a new Throughway radically rewrote the map, and drawing neat borders between space empires was seldom a fruitful exercise. Diplomatic treaties between governments preserved a handful of barren, meagre planets as a no-man’s-land claimed by both and neither. Nillitik had been one. Had been, past tense.

Nillitik hadn’t had a biosphere, or even an atmosphere. There’d been just enough mineral wealth to make the place viable for independent operations, but the main activity for the majority of the planet’s small population had been to evade scrutiny when meeting and trading. Cartels, smugglers and spies had all marked the place on their maps with approval. And then an Architect had turned up and twisted the planet into a spiral. Slightly under a hundred people had died, out of the ten thousand present when the vast entity had arrived in-system. Unique amongst the targets of the Architects, almost everyone on Nillitik had transport ready to get them off-planet in a hurry, though they’d mostly been worrying about Hugh, or their rivals. The event had been so bloodless that history books would probably not even remember to include Nillitik on the rolls of the lost.

Of course, just because so few actually died didn’t mean there were no ripples from the planet’s destruction. A lot of deals went south, a lot of partnerships dissolved, a lot of goods ended up without buyers, or buyers without goods. The destruction of Nillitik was like poking a muddy pond with a stick. All sorts of things were suddenly roiled into unexpected view. As a lot of suspicious people were forced to rebuild their lives, things were held up for a quick sale that might otherwise have remained safely out of sight. Including information.

Two worlds along from lost Nillitik on the alleged border chain was Hismin’s Moon, the sole habitable body of a spectacularly unlovely star system, and that was where the majority of trade had gone. Right now the moon was enjoying a prodigious visitor boom as what seemed like twenty planets’ worth of criminals and speculators descended on it to see what could be scavenged. And where there was something to scavenge, you found vultures. Specifically, the ship the Vulture God, captain one Olian Timo, familiarly known as Olli. And though there were plenty of legitimate reasons for the God to be conducting business out of Hismin’s Moon, Havaer happened to know that right now they were on the payroll for the Aspirat—the Parthenon’s intelligence division and his opposite numbers in the spy game. Which meant they were all here for the same thing.

Havaer had Kenyon, his second in command, wrangle a landing pad not too far from the God, and when they disembarked he wandered over to eyeball the ruinous old craft. It was the poster child for unlovely but, apart from vessels fitted out by the big core-world companies, that was practically standard Colonial aesthetic. Even Hugh’s own warships came out of the Borutheda yards looking like they’d lost a battle. Because back in the first war that had been humanity’s lot; always fleeing, always patching, never able to stop and build something new. Looking bright and clean and fancy would have felt like turning your back on everything your ancestors had gone through to get you this far.

The God was a salvager, meaning much of its shape was dictated by the oversized gravitic drive bulking out its mid-to-back, enabling it to seize on a far larger vessel, haul it about and carry it through unspace if need be. And they’d done good business due to their unusual navigator, Idris Telemmier the Int, who’d been able to reach those wrecks that had fallen off the Throughways, out in the deep voids of unspace. Except these days, as Havaer knew all too well, Telemmier was off doing something of considerably more concern to Mordant House.

Unless he’s here. A thread of excitement ran through Havaer as he turned the idea over. Hugh had no overt standing orders about the turncoat Int, because there was a war on and that kind of thing wasn’t going to help anyone. On a more covert level, if he could grab Telemmier without leaving fingerprints all about the place then his next review meeting would look decidedly sunnier. Make up for him letting the man get away the last time.

He paid the Hismin’s Moon kybernet for access to Drill 17’s public cameras and ran facial-recognition routines until he picked them up. There was Olian Timo. Not hard to spot with her truncated amputee form in that huge Castigar-built Scorpion frame she was so proud of, and everyone was giving her plenty of room. There was their Hannilambra factor, Kittering, who’d doubtless have all kinds of home-ground advantages to call on right now. There was Solace, their Partheni handler, without her powered armour but with a goddamn accelerator slung over her shoulder, as though that wouldn’t leave holes from here to the horizon through Drill 17’s thin walls. No sign of the prize, Idris Telemmier, though. Nor Kris Almier the lawyer, who was the smartest one of the crew in Havaer’s book.

‘Mundy? Sir?’ Kenyon prompted him. He and the other two in the team were strung out towards Drill 17’s airlock, waiting for him. Havaer nodded, feeling the tension rise inside him. He guessed he would end up head to head with one or other of the God crew at some point soon. Either against Kittering in a bidding war, or against Olli and Solace in a more traditional sort of conflict.

Not one he could lose, either. Not and keep his record clean and sparkly for the dreaded review. Mordant House—formally known as the Intervention Board, Hugh’s investigative and counter-espionage body—had a deep and abiding interest in this business. Someone was selling their secrets.

***

Chief Laery hadn’t looked well for half of Havaer’s life, but when he’d gone into her office for briefing before this latest mission, she’d looked mostly dead. She was an emaciated creature, reclining in an automatic chair with a dozen screens unrolled around her, nearly all blank now. He reckoned she’d just finished some multi-party conference, which was good grounds for looking exhausted and sour. With Laery, though, that was just her regular demeanour. She’d spent too long in deep-space listening stations in her youth, often without reliable a-grav. Her bones and body had never properly recovered and she needed a support frame to walk. Her mind was like a razor, though, and she’d headed up the department Havaer was in for all his professional life. She wasn’t a pleasant superior, not even one you could uniformly call ‘harsh but fair’, and on bad days her temper could overflow into malice quickly enough. She got things done, however, and she didn’t throw away tools she could still use. Which was why Havaer hadn’t quite been slapped over the whole freeing of Telemmier business. Simply arranging to save Hugh’s most precious world from the Architects wouldn’t necessarily have been enough to preserve him from her wrath, otherwise.

‘We had a leak,’ she told him, straight up. ‘Some fucking clerk on the political side. Not actually Mordant House but one with access through the Deputy-Attaché of you-don’t-need-to-know-which-goddamn-office. Whose own chief was decidedly lax about who got to see the transcripts of behind-closed-doors forward planning meetings.’

‘Leaked where?’ The Parthenon hung between them, because that sounded exactly the sort of spycraft they were good at. Not the actual dirty-handed stuff, but ideological subversion. There was always some quiet intellectual who secretly fancied herself in a grey Partheni uniform and doing away with Colonial graft and inefficiency.

Laery had her chair shift its angle, hissing in pain until she’d found a better posture. There were a couple of tubes in her arm, feeding her meds. If it was supposed to take the edge off, then she needed to get a new prescription.

‘To a creditor, if you can believe it. The same old. Speculation gone sour, money owed, money borrowed, respectable lenders to shabby spacer banks to something entirely more disreputable. When they came to call, some transcripts were put up as collateral. All of which is out now, and there’s someone else dealing with the up-front of it. But the transcripts made it onto a packet ship heading into the shadow border. Nillitik.’

Havaer blinked. ‘Nillitik is gone.’

‘Yes. And a great deal of stock-in-trade that might have remained decently buried is now being flogged off cheap to make good on those losses. So our dirty laundry is on the market, sources say. Go gather it in. And if you can identify any other buyers, even bring them in or neutralize them, then that’s a bonus.’

Havaer nodded, already thinking forwards. He’d run missions along the Hanni shadow border plenty of times before, even set foot on lost Nillitik once or twice. All well within his competence.

Still… ‘This is where you ask, why you,’ Laery prompted him.

‘It’s got to be someone,’ Havaer noted mildly.

‘Intel suggests word has got to the Parthenon and they’re the frontline buyers. Now we can always outbid the Pathos, but we can’t necessarily out-punch them if they decided to kick off. And even though everyone’s tiptoeing around the war we’re supposedly no longer on course for, a major action out in the shadow border might just be something they think they can get away with. And you, Menheer Mundy, have had some recent dealings involving the Parthenon, so your record says. Not entirely creditable ones. So perhaps you would relish the opportunity to make good on that.’

Havaer felt his internal dispenser feed him some heart meds like a steadying hand on his shoulder. Might be about to walk into a shooting war.

‘A team’s been assigned to you. Be diplomatic. Be firm. I’d rather you didn’t have to kill anyone but sometimes you can’t mine without explosives. Above all, retrieve the data, preferably still sealed.’ Laery fixed him with her skewer gaze. ‘Questions?’

‘Can I ask what intel got leaked? How desperate are they going to be, to get hold of it?’

She stared at him for a few long moments. ‘Above your pay grade,’ he was told. ‘Or it better be, because apparently it’s above mine.’

***

Drill 17’s public spaces were thronging, meaning those areas set above the actual mining work that was the place’s ostensible raison d’être. Every little alcove and showbox of a space was filled with people doing some kind of business. Hannilambra were everywhere, very much running the show. Havaer observed the characteristic slightly strained look of humans trying to follow what their earpieces were telling them, or fighting to separate the audio of their translator’s voice from everyone else’s. A big Castigar, war-caste, wound its serpentine way through the bustle, shoving smaller species aside with a sinuous surge, its crown of eye-tipped tentacles weaving around.

Kenyon deposited the rig’s floorplans into their shared e-space, marking out the place their factor could be found, along with a few other sites of interest. Lombard, their technical specialist, was a hypochondriac of the first order and his attention had been snagged by a travelling Med-al-hambra booth. The Colonial charity was supposed to bring Hugh-guaranteed meds to spacers at the fringes of the human sphere, but Havaer wouldn’t have trusted anything on sale here.

Reams, the last member of the team, stopped abruptly. Havaer had detailed her to link with the kybernet and get them up to speed with any local developments. It would have been awkward to ask for their factor and find out that he’d been knifed the day before, for example.

‘Architects,’ she said on their crypted channel. And, realizing that sounded unduly alarming, ‘Not here. They’ve wrecked Cirixia.’

Since reworking the world of Far Lux and then being deflected from Berlenhof—an event all four of them had disturbing personal recollections of—the Architects hadn’t been idle. They’d taken out Ossa and Nillitik, and pitched up above a world that was still just a string of numbers because the joint Colonial-Castigar colonizing effort hadn’t agreed a name yet. There hadn’t been Earth-level losses, but at the same time the pace of their activity was decidedly brisker than in the first war. And now Cirixia.

‘Where the fuck,’ asked Lombard, ‘is Cirixia? I never heard of it.’

Reams forwarded the newstype to everyone and they all slowed their progress to digest exactly what it meant. It was months-old news, apparently, only reaching the Colonial Sphere now, because reliable info was always slow to crawl out of the Hegemony, where the planet was.

‘Huh,’ Havaer said. ‘There’s a thing.’ They’d had Hegemonic artefacts at Berlenhof, still preserved in the inexplicable magic that enabled their transport from planet to planet. When the Architect had turned up over that world again, the Partheni had taken out those artefacts to protect their lead warship, the one carrying Telemmier and the other Ints. And this time it hadn’t worked. A straight-up guarantee about what the Architects would and wouldn’t do had turned out to not be worth the paper it wasn’t written on. In fact, so he’d heard, the Architect had sent… things aboard the Partheni vessel with extreme prejudice, confiscated the damn artefacts, and then proceeded to trash the ship. The Architects weren’t only back, they were making up for lost time, losing patience with the universe.

And now a whole Hegemonic world, with who knew how many humans and others living on it, was gone. During the first war, it had been humanity in the spotlight. Other species had pitched in to help but the Architects had definitely been concentrating on human worlds. This time, it appeared they weren’t discriminating.

Makes you wonder just whose backyard they were redecorating in the fifty years we didn’t hear from them. Nobody doubted there were species out there that humans had never met and which the Architects had picked on, likely causing many of them to now be entirely extinct. The enigmatic Harbinger Ash claimed to be the last of one such lost race. The Naeromathi and their Locust Arks were a spacefaring remnant whose worlds had been entirely reworked.

‘One less problem for us to worry about,’ Kenyon suggested darkly, as they crossed into a larger space given over to a bar. The Skaggerak was probably the nastiest R&R at Drill 17, thronging with human and Hanni and a handful of Castigar. Rotary drones wobbled overhead delivering drinks that they only spilled half of. You could get quite drunk in the Skaggerak just sitting around with your head tilted up and your mouth open.

Havaer directed Reams to get a round in, and then Lombard to make sufficient mundane enquiries of the kybernet and local businesses to establish their cover as itinerant spacers. His eyes swept the room even as he cocked a brow Kenyon’s way.

‘Nobody’s going to be in a hurry to join them now the cultists can’t promise protection anymore.’ And that was Kenyon’s obituary for however many thousands or millions had died, on wherever the hell Cirixia had been. From a strictly departmental point of view, it was a fair assessment. A number of human worlds had taken up the Hegemony’s offer of protection, during the war and after, the price of which was always complete subservience to the bafflingly ritualistic Essiel. Becoming a clam-worshipper was probably less attractive if you didn’t have their shell to hide behind, though. The Originator tech that the Hegemonics had formerly used as a magic talisman against Architect attack was now only a speedbump since the monsters had returned. They still wouldn’t destroy the things, apparently, but they’d aggressively remove them from a ship or world, and then get on with their cataclysmic work anyway.

It wasn’t hard to miss the big old frame that Olian Timo used. Everyone moved out of the way when she came in and headed across the room. She passed close enough for Havaer to touch her, and he just eddied aside with the crowd. In the bubble of the hulking Scorpion she was a diminutive figure, with stumps for one arm and both legs, but her pugnacious attitude more than made up for it. She didn’t notice him as she stomped over to rejoin her two confederates, Kit and Solace. All three were very much on edge and Olli looked particularly punchy.

The opposition. The professional part of his brain was brewing plans and counterplans: what to do if they ended up going head to head? How much of a threat was that monster of a work-frame? Was there a pack of Partheni battle-sisters ready to rush in at Solace’s word? He checked with his team. Kenyon had made contact with the broker and was negotiating for access to the seller, Reams backing him up. Lombard was fishing to intercept comms from Timo and the others, but getting nothing of use. Havaer suddenly had a strong desire to just walk over there and take a seat, chew the fat, talk over old times. With that mob it might actually work, but from a tradecraft point of view it would likely look bad on his record.

He had a few brief heartbeats in which to hope they were merely adrift here, but he’d let Timo’s sour expression fool him. He should have remembered she always looked like that. Without warning, the three of them were on their feet and moving off purposefully, and he realized they’d used their head start well. They were already ahead of him.

Excerpted from Eyes of the Void, copyright © 2021 by Adrian Tchaikovsky.